Mars' Orbit: What We Know About Earth, Venus, and the Other Planets

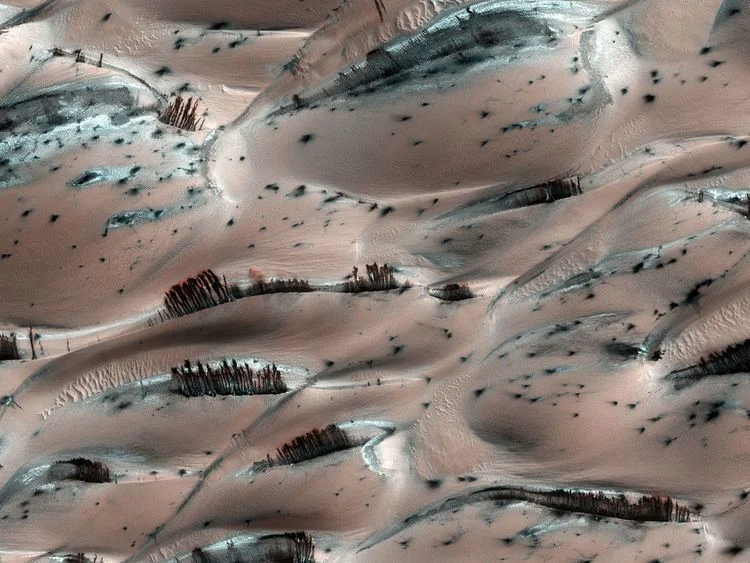

Okay, so Mars got a closer look at an interstellar comet. Comet 3I/ATLAS, to be precise, discovered July 1, 2025. The ESA's ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO), hanging out around Mars, snagged some observation data that improved the predicted location of the comet by a factor of 10. Ten times more accurate. That's the headline. But is it really that interesting?

The Martian Advantage

Trajectory observations are usually confined to Earth-based observatories or near-Earth orbit (think Hubble, Webb). Getting data from Mars is… novel. The Mars probe got about ten times closer to 3I/ATLAS than telescopes on Earth. That’s a geometric advantage. Triangulation between Earth and Mars helped refine the comet’s path. Fine.

The comet zipped past Mars at roughly 250,000 km/h. Fast, but not unexpected for an interstellar traveler. The CaSSIS instrument on the Mars orbiter did the observing. Astrometric measurements from TGO were officially submitted and accepted into the Minor Planet Center (MPC) database. This is apparently the first time measurements from a spacecraft orbiting another planet have made it into the MPC. (You have to wonder how much of a bureaucratic hurdle that was.)

Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) is also observing 3I/ATLAS after its closest approach to the Sun. Data from Juice's observations are expected in February 2026. So, more data is coming. But what are we actually learning?

Data, Data, Everywhere, But What Does It Mean?

The core argument seems to be that using a Mars-orbiting probe improves trajectory prediction. Makes sense. More baseline, better triangulation. But by how much? A factor of 10 improvement in location prediction sounds impressive, but what was the initial uncertainty? Was it kilometers? Hundreds of kilometers? Without knowing the starting point, the "improvement" is just a number.

And this is the part of the report that I find genuinely puzzling. They improved the predicted location. Not the observed location. So, they refined their model of the comet's trajectory. That's useful for future observations, sure. But it doesn't tell us anything new about the comet itself.

We know ESA routinely monitors near-Earth asteroids and comets. They’re even prepping the Neomir mission to spot solar-approaching objects and the Comet Interceptor mission to study comets, potentially interstellar ones. So this observation fits into a larger pattern of comet monitoring.

But here's the thought leap: how accurate are these models, really? We’re talking about an object traveling at 250,000 km/h across interstellar space. Tiny errors in initial measurements could compound into massive discrepancies over time. Is a factor of 10 improvement enough? It feels like patting ourselves on the back for incremental progress in the face of truly astronomical unknowns. How far off would the initial predictions have been without the Mars data? 100,000km? A million?

So, What's the Real Story?

This feels like a PR win masquerading as a scientific breakthrough. Yes, using a Mars orbiter for astrometric measurements is a clever trick. But the real value lies in the potential for future discoveries, not in the data itself.

-

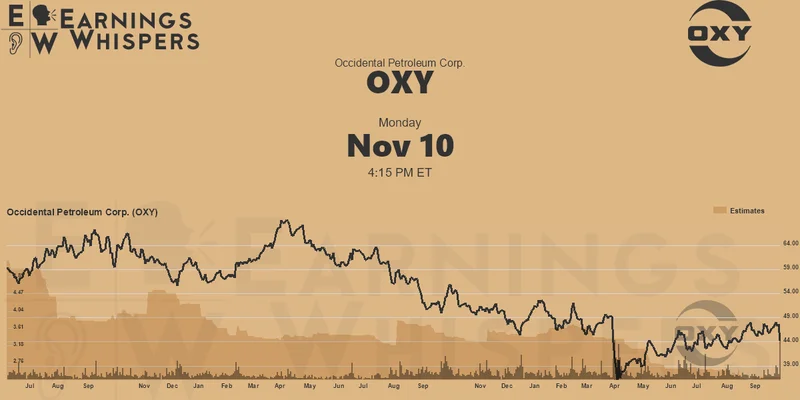

Warren Buffett's OXY Stock Play: The Latest Drama, Buffett's Angle, and Why You Shouldn't Believe the Hype

Solet'sgetthisstraight.Occide...

-

The Business of Plasma Donation: How the Process Works and Who the Key Players Are

Theterm"plasma"suffersfromas...

-

The Great Up-Leveling: What's Happening Now and How We Step Up

Haveyoueverfeltlikeyou'redri...

-

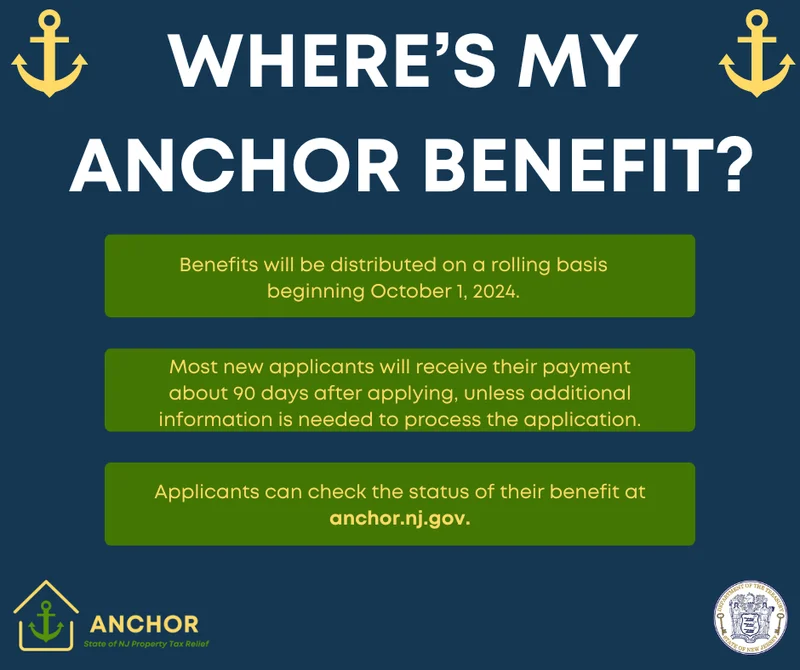

NJ's ANCHOR Program: A Blueprint for Tax Relief, Your 2024 Payment, and What Comes Next

NewJersey'sANCHORProgramIsn't...

-

The Future of Auto Parts: How to Find Any Part Instantly and What Comes Next

Walkintoany`autoparts`store—a...

- Search

- Recently Published

-

- Google Stock: Berkshire Hathaway's Billion-Dollar Bet and What We Know

- CoinMarketCap: Crypto Prices, Bitcoin vs. XRP, and What's Real

- Indigo: What's the Story?

- Daniel Driscoll and the Army Overhaul: What It Means for the Future of Defense

- Mars' Orbit: What We Know About Earth, Venus, and the Other Planets

- Firo Hard Fork: What to Expect and Why It Matters

- USAA Insurance: Car, Life, and Health—What We Know

- Nvidia Stock: Huang's "Incredible News" vs. What the Price is Actually Doing

- Bitcoin's Bear Market: Price Trends and What We Know

- Hyundai's Labor Lawsuit: Child Exploitation Allegations and Industry Impact

- Tag list

-

- carbon trading (2)

- Blockchain (11)

- Decentralization (5)

- Smart Contracts (4)

- Cryptocurrency (26)

- DeFi (5)

- Bitcoin (32)

- Trump (5)

- Ethereum (8)

- Pudgy Penguins (7)

- NFT (5)

- Solana (5)

- cryptocurrency (6)

- XRP (3)

- Airdrop (3)

- MicroStrategy (3)

- Stablecoin (3)

- Digital Assets (3)

- PENGU (3)

- Plasma (5)

- Zcash (6)

- Aster (5)

- investment advisor (4)

- crypto exchange binance (3)

- SX Network (3)